Scottish Business Archive

Cataloguing archive collections held in the Scottish Business Archive has been a significant factor in shaping my arts practice. Recently I completed the cataloguing of the Blackie & Son Ltd collection, a publishing company based in Glasgow. The process involved assessing the value of the collection through appraisal, and cataloguing to series level. The drawings and collages I created whilst cataloguing led to the creation of Art Production Records in the artist archivist archive. These bundles have no fixed state, can be arranged however an audience chooses, and preserves the functional behaviour (studio practice) of the Artist Archivist.

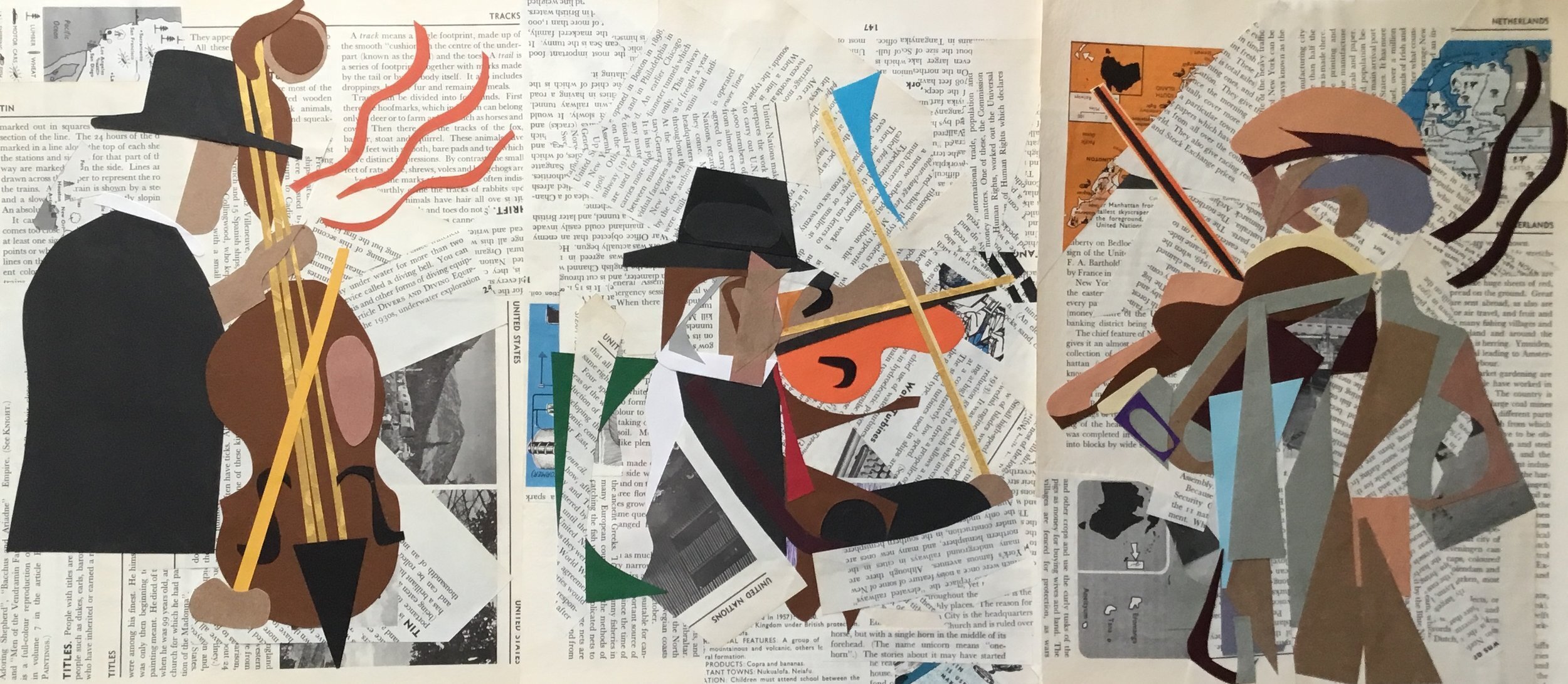

The first artworks created were based on the first things I catalogued, the business photographs. These range from factory scenes, staff portraits, exhibitions. I selected prints from within the booklet titled ‘Complimentary excursion to Killin’ (1925) to start with. Overlooking Loch Killen, staff were entertained by a small orchestra. I created paper collages in an attempt to capture discreet movements of musicians and the shape of music. However, fairly quickly I grew frustrated by their static nature. Even when combining all three collages together in a mural format, the background hinders any sort of valuable movement.

The Blackie & Son Ltd archive contains a complete set of Blackie retail catalogues . These start from 1817 until the company ceased trading in the early 1990s. The catalogues record the publication title and description of contents, author, prices and occasionally illustrations. They preserve the subscription model used by consumers. Publications were retailed within the United Kingdom and exported to different parts of the British Empire. I described the catalogues on Archives Hub briefly listing their circulation date, genre of publications listed within, intended country for retail, and the record type (ie: notebook).

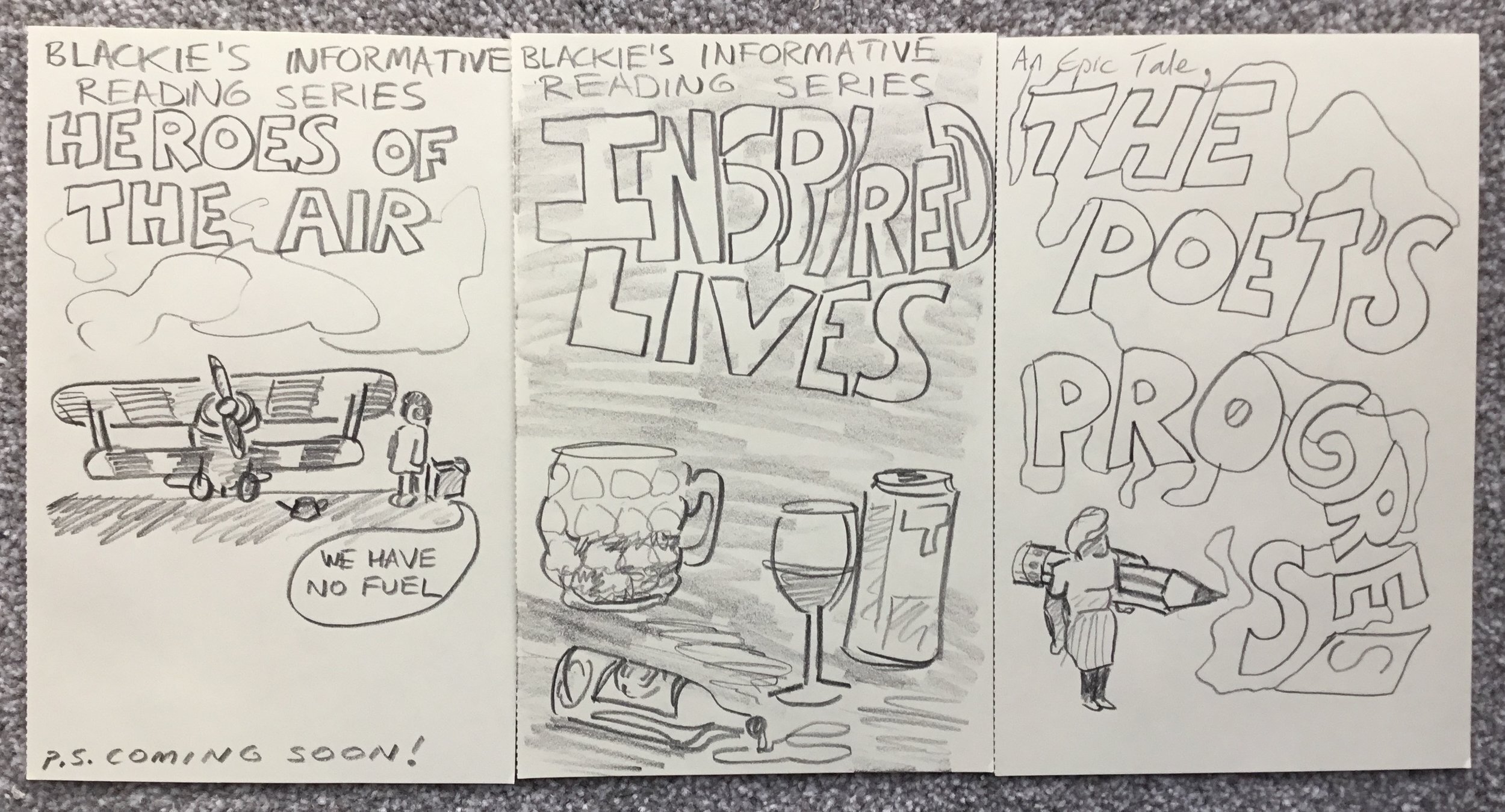

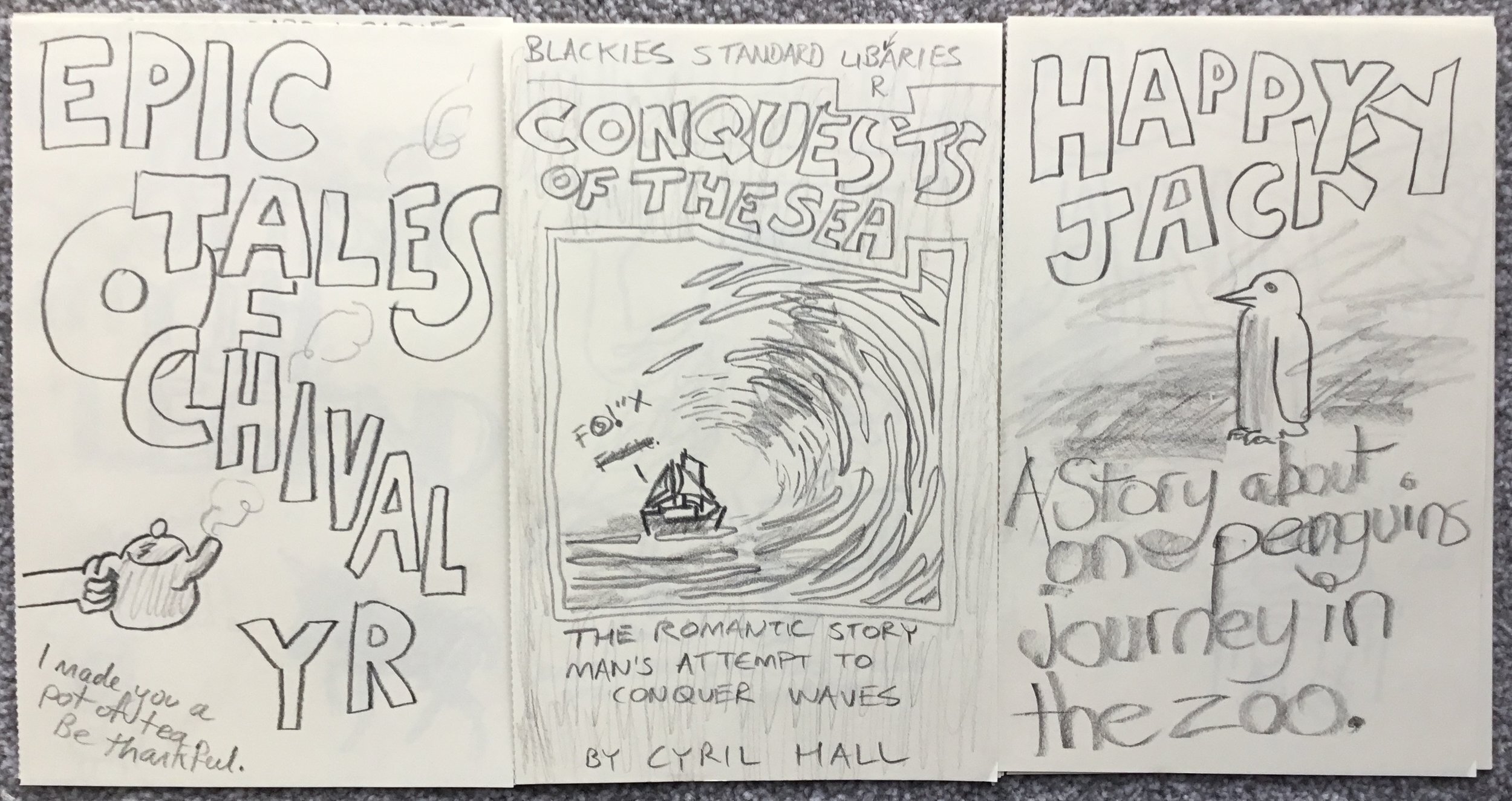

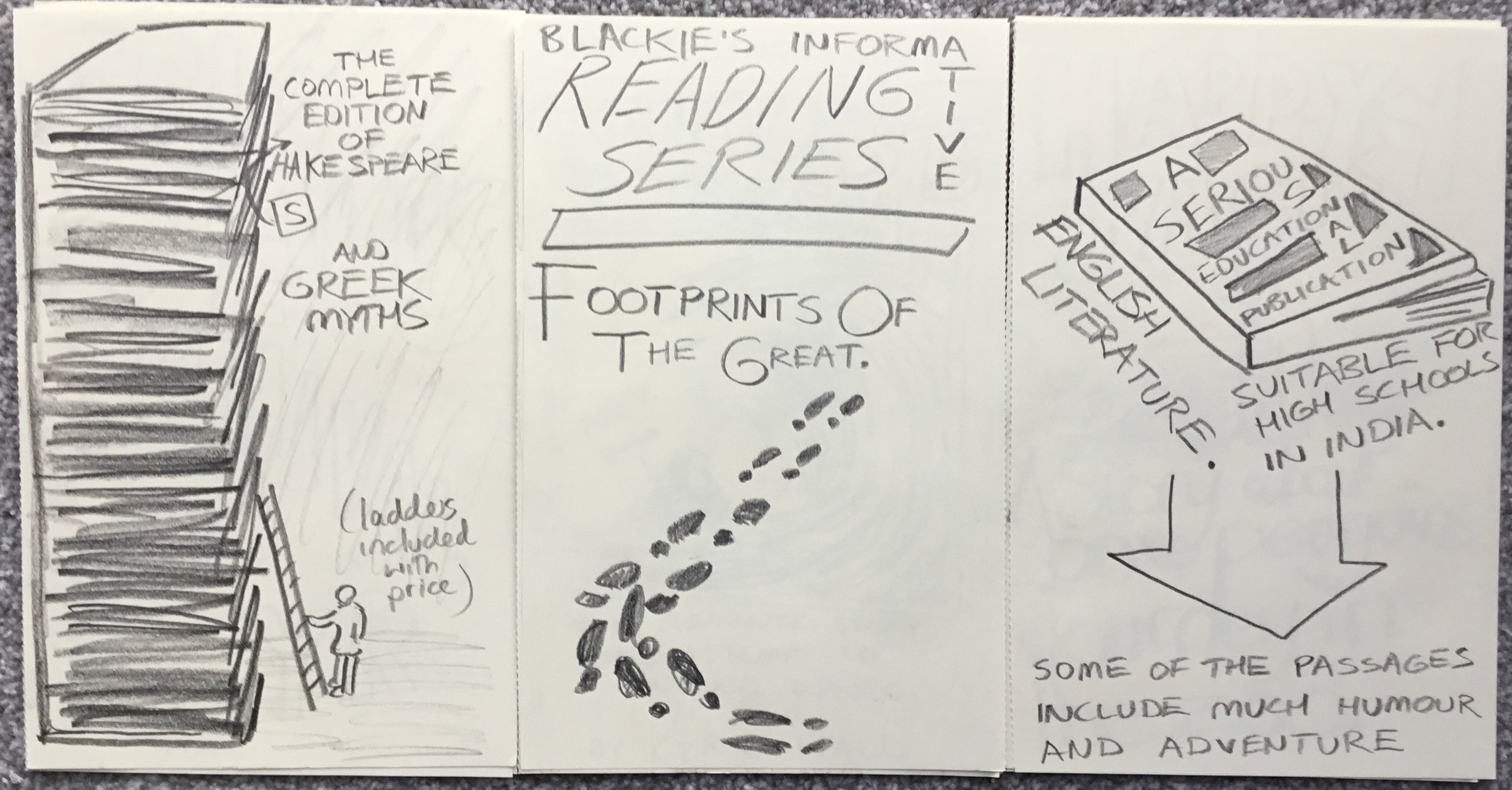

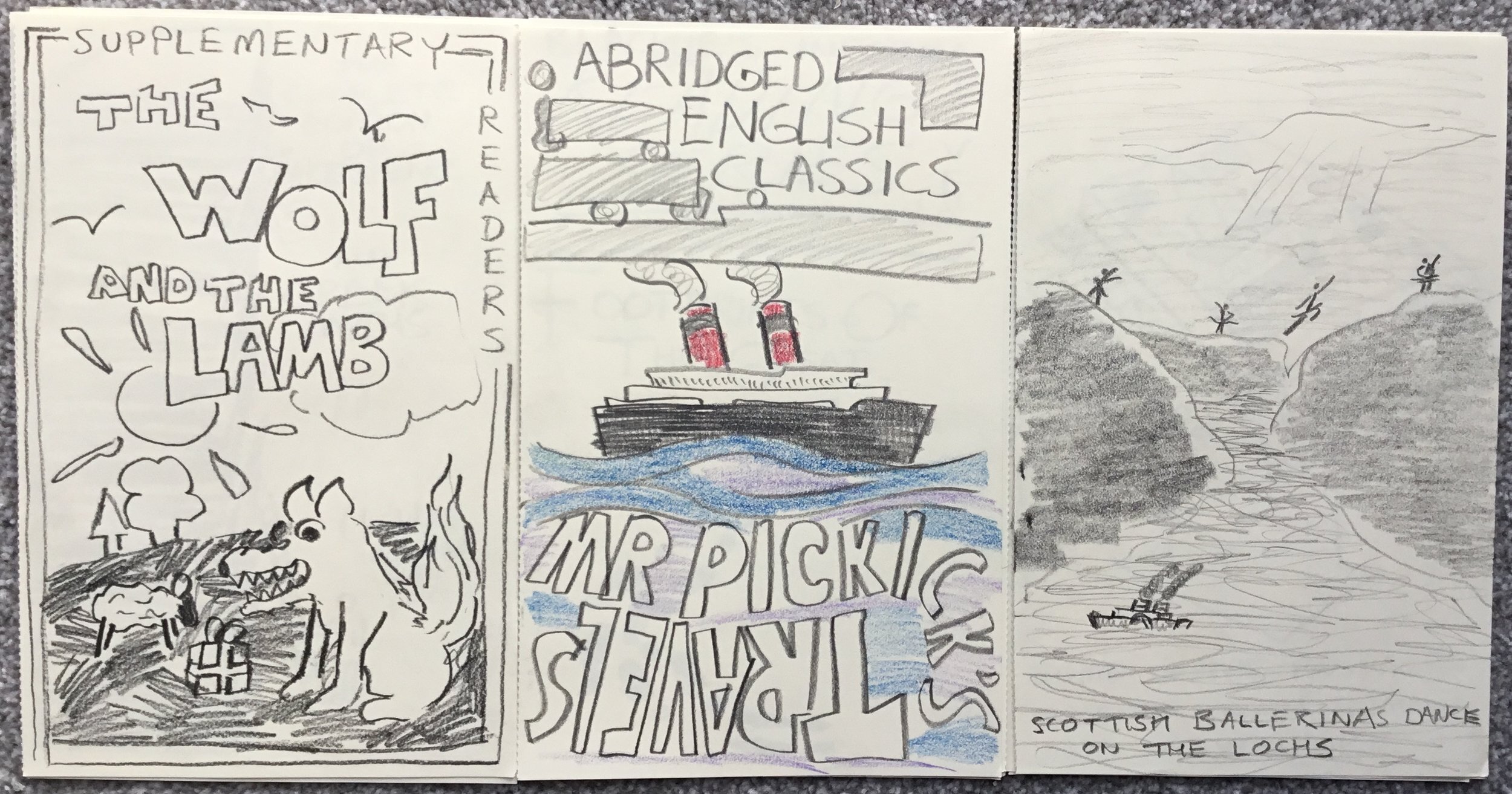

The drawings you see here on this article are a selection of 10 minute sketches from using information held within these records. The books were targeted at young adults, containing stories about international exploration whether in the polar regions or rainforest. Stories of heroism in the air or spy networks within the newly formed Soviet Union. The stories are told from the British perspective, characters from the Royal Navy or heroic white male explorers. the context changes but the vision is clear. The stories educate the younger generations through the perspective of what British institutions wanted the audience to read.

A significant drawing I created is titled ‘The Poet’s Progress’ - that is what stimulated my thoughts. The drawing represents a question about the role of the publishing company exporting information within the British Empire. It comes from a 1920s catalogue passage that states ‘suitable for High Schools in India’. Who decided these European or British poems are suitable for educational purposes in an entirely different culture? This doesn’t appear to be a cultural exchange of ideas rather this is evidence of an authority imposing their opinions and shaping the thoughts of others. This also evidences how the English language was exported internationally. Through violence and trade, British Empire was an intrusive institution. It imposed itself culturally on others, while the Blackie company may not have had this direct intension. They participated in a normal practice for that era. It benefited from and exported ideas from the leading global superpower. When we consider the present challenges with data sharing, information manipulation, an era where the fact is under attack – its not altogether different than what it was 100 years past. Instead this information war of control / ideas is waged online rather than through physical books. The artwork continued to evolve the more I catalogued the Blackie collection. The paper collages represent themes I was exploring in the Poet drawing and wider visualisation of the cataloguing process.

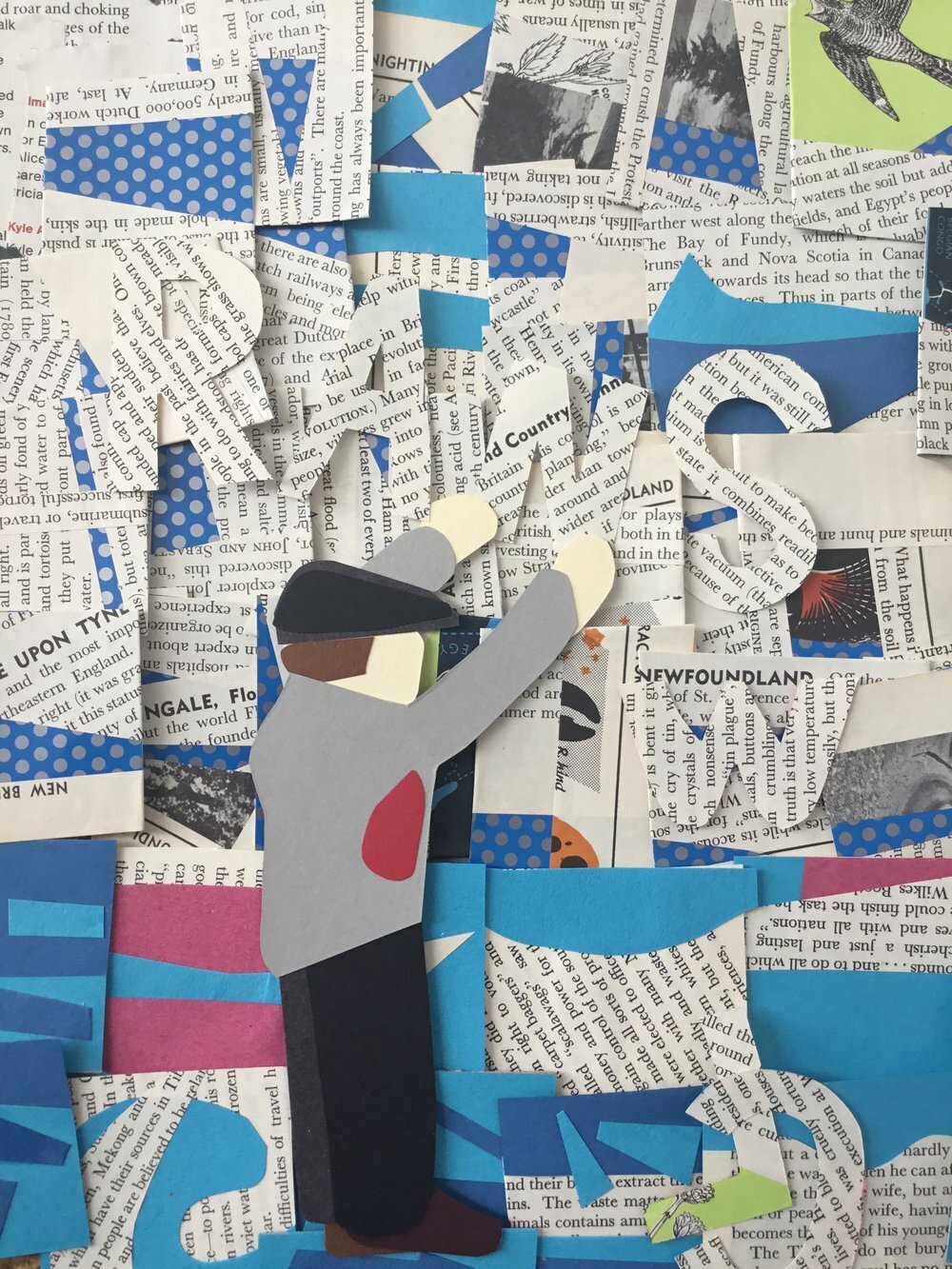

What is the value is retaining the companies’ production records? What value is there in knowing the amounts of books produced? Or the typeface used in publishing? I started to create production records of my own in paper collage. A bundle of paper pieces sit inside a box. They are not fixed, they can be shaped in what ever way an audience wants to shape them. This particular paper collage shows a poet surrounded by an encyclopedia of information, creating and selecting poems for publication in India. This method of working is far more beneficial to my art practice than creating fixed art objects. I created another bundle of production records, arranged to represent an archivist surveying, appraising, and cataloguing records. The background is landscape created via collaging National Geographic magazines, the landscape is part of my collage subject files, created for no purpose other than to create something. This opens questions about the fixity of art records within the Artist Archivist Archive, and also highlights how researchers operate. Drawing on information from multiple sources to create a conclusion

James Finlay Co Ltd

Shifting through the artist archivist archive, located two paper collages which is where the entire concept for this artist archivist was launched. Based upon two photographic prints showing scenes from South East Asia tea estate scenes c1910-c1920.